ENJOY ICE CREAM AND DESSERT TREATS, ALL WHILE SUPPORTING GUYANESE WRITERS

Dampened by the 2005 flood, the pages of my grandmother’s recipe cards had been stuck together. But I still persevered, because my life depended on being able to decipher the contents of the cards.

Something had gone wrong. That much was obvious. For my migraines had blossomed into strange memories. Memories of midnight walks that end at a crossroad with a strange, lanky man. Or memories of a pre-dawn swim in a creek, with pearls braided into my curls.

I bit my fist to silence a scream of frustration.

The baths were my way of protecting my mind. Something my father had advised – my mother used to do it all the time. It’s a home remedy, what’s the harm? Tucking the card back in, I glance at the array of emptied energy drinks, then back at the old wall clock.

It was three minutes to three in the morning. Setting the box down, I snap the drawer shut. Already, the night is almost over. If I could keep my eyes peeled until three, I was gold. Venturing to the kitchen for another can of energy drink, I count the seconds. One, two, three, four, five.

I cock a hip on the kitchen counter and look out through the half opened backdoor, drink in hand. Even in the dark, our tiny spot of paradise is stunning with its virgin nature. The village is silent... except for the occasional hum of a drunk man stumbling home and the orchestra of nature. The hooting of owls. The crying of cats. The croak of crappos.

Turning to head back to my room, there’s a tightening in my neck – spine stiff and burning. Fight is not an option. Feet, one after the other, hands unlocking the doors. I want to scream, but my tongue stays flat and my lips thin.

The door creaks open. The cool night breeze is a solemn greeting. Fear grips me. Water fills my eyes and saltwater rolls down my cheeks. The dirt road is rough beneath my feet. Pebbles and bricks pressing into soft skin. But my puppeteer doesn’t stumble with me. The guide is smooth, though the walk makes me bleed.

Wide, red dirt rolls up the hill and its surrounding bush begs to the imagination, whispering of creatures known and unknown. The dark is all-encompassing and all-chilling. None of the other times felt like this. They had all been easy and dream-like. What lurked in the shadows, so secret and old? Yellowed claws, sharp eyes, and primeval hunger. What was my place here?

My feet pause, arms swinging from the sudden loss of momentum.

I can finally move my head, but nothing below my shoulders. My mouth unhinges for a scream, deep from stomach. Help. Anyone. Help me.

“You are noisy tonight, Archiver.”

A man towers over me. His eyes reflect the moon, greyed and sliver. His lips spread into a wide, genuine smile. “Oh. Finally. You have his look, fierce. You’re ready to take post. I wondered how much longer we would have to wait.”

“P-Post?”

The man nods, leaning back, with limber arms folded as he looks at me. “You are young. The last one came to us older, but perhaps it is time for youth to stand centre.”

“Let me go.” I snap, baring my teeth.

The man laughs. “Full of fight! You will need it for what’s ahead.”

“What's ahead? Beside me knocking you off your feet the moment I can.”

“Ahead. A head. Funny thing words. How we use language like a song. I know many songs without language. I know songs just made of,” he taps his chest, sound pretty like flute echoes, “Bones. You, my dear Amani, are our new archivist. You keep our tales and stories; you pass them down until the next one. It is tradition. It is destiny.”

“And if I don’t?”

“My dear girl, whatever made you think you had a choice? We begin tomorrow.”

I awake in my bed, mud caked on the soles of my feet and my hand covered in black ink. Around me are pages upon pages of senseless script. Rays from the rising sun burst through my open windows, burning my eyes.

***

“Good morning, I’m here to see Mr. Arnold Palmer. I’m his granddaughter, Amani.”

The nurse takes me up to his room in the hospice. It’s a nice, private room with its own bath.

Pa was going to die soon.

This fact did not make it easier for those of us who loved him. He was ninety-seven but it still felt like too short a time. When I walk in, he’s sitting up, narrowed eyes looking down his half-moon glasses as he read the newspapers.

“Morning Pa.”

He shifts his gaze to me – one milky eye and one brown like mine. “My favorite child. Come, closer. Let me look at you good. You putting on some weight?”

And you losing some. “How they treating you here?”

Closing his newspapers, he raises a shaky hand as if to show, so-so. “Could be worse, could be better. To complain is to spit in God face.”

I keep the conversation going for a while. Trying to not make it seem like I only came here to ask about his wife. Dad doesn’t talk about his mother much. She’d died too young. The box of her things he’d given me had taken a lot of persuading – months and years.

“I wanted to talk about Granny.”

Pa’s face takes a turn, twisting the pelts and lines and squeezing his eyes shut. “My baby. My Evangeline. You remind me of her, you know. She had the same smile and eyes.”

“Did she ever mention hallucinations when she took her baths? The special ones.”

“Hallucinations? No. Never.”

“Pa.”

“Evangeline never had any hallucinations. She was obsessed with old world medicine, with taking baths and drinking strange teas –”

“Teas?” I hadn’t seen any cards for teas.

“Nonsense, Nini. It’s all nonsense.” Pa pats my hand. “My daughter had eccentric rituals, but be assured, they held no power.” His tone sounds forced, expression closed off.

Pa is lying to me.

I see it in the turn of his face and the quivering twist of his lips. Most of all, I feel it in my gut – like a sinking, stabbing ache. I feel betrayed by his lie. Nonsense. The word coming from his mouth makes my ears ring. Those hallucinations were not nonsense. Nevertheless, I squeeze his hand and promise to visit again.

When I get home, I go straight to the box and properly rifle through it.

There are books, embroidered handkerchiefs, dip pens and all sorts of paraphernalia. I see a little into the illusive life of my grandmother I’ve never known. I see that she kept diaries and drew in them, like I do. I see jewellery labelled “favourite” in her loopy script. There are two smaller boxes in it, much like the one the index cards for the baths were in. The first one has pastries.

The second has the tea.

Her cursive fills the cards. There are even little notes on some of them, substitutes, and warnings. Too much thyme in the purification tea just makes the base for cook up rice seasoning. Finally, one for sleepwalking. All the herbs can be found in our garden or the neighbour’s.

Collecting them takes the longest. Some of them I have to call my father for, because I have no idea what a Porcupine Batty is. They all sit in a calabash, as if staring at me, waiting for me to do something with them. The card tells me to add salt water to them. Either from the sea or salt and rainwater. No boiled or distilled: she noted in curly red ink.

Hands on my hips, I grin at my luck. Take that for destiny!

The barrel by the gutter is full and chill, even in the warmth of the afternoon sun. I fill a cup of water and go back to the kitchen to finish off the tea. It’s tedious. Evangeline insists on it being first mixed by your fingers. Then transferred to a mortar and mashed to mush. The sight isn’t pleasant and I wonder why I can’t just blend it and drink it with some coconut milk and sugar and call it day.

Then I remember that this is ritual. And ritual is to be followed. The dead laid their rules with reason and I am obliged to follow.

Even if the mixture looks like sewage water.

According to the card, I don’t need much. Two sips will suffice. Pressing the cup to my lips, the awful smell burns my nose. But I chug a mouthful anyway, choking back vomit.

I immediately grow dizzy. Stumbling to the couch, I collapse belly-first. Face to the side, I stare at the spinning world. In the shapes, something walks forward, hand stretching to me – I scream and try to thrash, but my stomach revolts. Down my chest, vomit, tinged the colour of the dark-green tea, flows.

The strange thing holds my arms and frowns down at me before speaking, “You block your path.”

Dad finds me covered in vomit, catatonic on the floor. In a panic, he drives us to the hospital. After the examination, the doctor looks me up and down, before proclaiming that I must have been drinking. I'm then sent home with a card of paracetamol and good wishes.

That night, my father looks at me softly with a kindness that denotes disappointment. He kisses my forehead after I wash and begs me to sleep through the night. I want to tell him it isn’t up to me. But I don’t want to be sent to Berbice, so I turn over and try.

My attempts at normal sleep are futile.

That much is apparent, when I’m once again walking until me feet bleed and staring up at twin moons. This time, though, I have a pen and paper.

***

“…so you don’t capture children and eat them?”

The moonwalker sighs, crossing one toothpick leg over the other. “Too chewy for my tastes.”

My pen stills. I eye him cautiously from beneath my lashes. He laughs at my suspicion. A echoing, deep sound that sends a bat out of a mango tree. My job– as it would seem – is to be a recorder of the lives of mythical creatures. The moonwalker hands me a tome and taps his talon on the index.

“Moonlight stories are a thing is the past,” he says. “So we have to resort to other methods of keeping a memory of who we are. To keep us... alive”

I finish off the last story he had narrated to me. It was a story about dimension hopping – explaining the moons in his eyes, the ability to stretch to the heavens if need be. An alien – lost and seeking home. It was all too poetic.

“So you're saying that if I burn this book, you all die?”

He smiles. This one is unlike the others. This one has teeth. White. Sharp. Aching to tear. “You can try. Did you enjoy your tea?”

Ice rolls down my spine. “Was it you who found me?”

“Not me.” He stretches a hand to one of the higher mango tree branches we’re currently sitting under. His elongated fingers pluck a red mango and he peels it with his front teeth, before biting into the juicy flesh. “But we are legion and many. All spindly roots of the same tree.”

The thought disturbs me. I’m standing on a tight rope above a pool of caimans who seem to have been starved for two days. My dress is soaked in blood and guts, dripping down to tempt them. One twist of an ankle and I fall.

“This will be every night?”

“Yes.” The mango picked clean to the diminished seed, he hurls it into the bush across the street. It hits something with a dull thud, followed by a howl, and an old common breed dog limps out with his fangs bared at us. I almost say sorry before the moonwalker cuts me off. “But we take care of our own. Not to worry, we hardly harm our Archivers.”

“Hardly? You’ve harmed them?”

“Besides the point.” His hand waves. “Tomorrow, it’ll be a fair maiden. Try not to eat any fish.”

Besides the point?

The next night is a cloudy one. Sitting at the edge of the river, I keep my legs folded beneath my bottom as a smiling woman plants her elbow at the edge of the shore. There are pearls in her hair and she has rich, deep skin. With her looks, she could have been on the cover of any Western magazine. The golden comb in her hair keeps her curls out of her face.

“Did you become or were you born this way?”

“I became. Though, there are those who were born.” Her tail makes an appearance, wide and glittering in the moonlight. Everything about her is both temptation and damnation. “I drowned myself on my honeymoon. Death was better than being married to my husband.”

She mentions him being an older man. White haired and mean spirited, but rich. She says that had he not been so violent, she would have overlooked his sins of age and cruelty. Until he turned it on her stepdaughter. He had been a fan of the sea. The Fair Maiden tells me about cajoling him to take a midnight sail. They sailed out from his property on Berbice, out into the sea black as the night. She had planned it out; a bottle of special tea and a knife if the tea was too weak.

What she had not catered for, was his strength – turning the blade over to her as he choked on his own blood. “The sea drowned him,” she says with glee, “but it welcomed me.”

“Was it a painful transition?”

“It was.” Her eyes completely black out, whites gone. “But the older maidens are kind, we welcome each other with ease. So whatever pain is overshadowed by the kindness during the process.”

“Do you travel in groups?”

“Sometimes.”

“Do you kill?”

“Sometimes.”

Weariness fills me. Before I know it, I’m leaning forward. The tome lays forgotten at my side. My head is bowed, as if weights are attached to it. Before I know it I am submerged in a thicket of fog, pulling me down into the icy depths.

At first the water maiden’s face smiles up at me in a warm, welcoming way. But then, through my fog, the smile turns into two sets of spindly daggers for teeth, as her jaw unhinges to take me.

Something scratches my back, twisting the material of my nightdress and pulling me back and away. My heart almost aches, until I’m pulled back far enough to feel the air around me. My eyes widen. She was going to kill me!

The maiden gnashes her teeth. Her beauty seems to have evaporated in the exchange. The lids of her eyes are gone. The richness of her skin gives way to a sickly, greyed composition of scales. Water splashes as she disappears, going back to the depths.

“That was very stupid of you. Didn’t the moonwalker warn you about fish?” it’s the voice of the being that had come to me before. Its hold stops me from turning to see it.

“The moonwalker,” I spit with rage. “Told me that I would be safe. That you monsters didn’t harm your precious Archivist.”

“We aren’t suppose to.” It corrects. “But who eats fish to visit a water maiden?”

“I didn’t! Jesus,” I wiggle and scratch at the being. It sighs then drops me. Rubbing my bum, I turn to see nothing but blinking orange eyes in the shadows. The blackness shifts but holds no specific form as it floats before me; mass of mist. “I didn’t even eat today! All I had was some breadfruit fries and then a roasted chicken.”

“Took any vitamins?”

Vitamins? Hands akimbo, I answer. “Well, my usual of iron, biotin, omega-3 –”

“Got it deh!” it laughed. “What are omega-3s made of, dear Archivist?”

A silence passed, at first a hushed moment before it grow pregnant. Shame filled me. How was I so careless? Turning, I picked up the tome and made my way back with my chuckling shadow friend at my heels.

“Have fun tomorrow!”

“Tomorrow? Who am I documenting tomorrow?”

But it leaves nothing but laughter in its wake and my walk home is a lonely one.

***

“Hi, Pa.”

The old man smiles at me through his oxygen mask. His hand raises to wave me into the small room he’s occupying. Frankly, it’s the best one. There’s a little veranda that overlooks our garden and the expanse of trees and clean roadways. But he can’t move anymore.

The nurses say we ought to keep an eye on him. Even with an extra eye, my father warns me not to get my hopes up; “But it’s soon. Soon.”

I don’t want to think of impending death, though its apparent that’s why he’s home now. For now, I sit with him and we listening to old LPs and telling me about his youth.

These were stories I’d heard many times before, but hearing it again from Pa never got old. He falls asleep eventually and I slink away. My father tells me to stay and watch him – since he has night shift. I check on him during the night to see him resting still, finger on pulse, before I kiss him and the forces that guide me, take me for another walk.

I had asked the moonwalker why I couldn’t just have them in my home. He had looked horrified.

“Never invite one of us to your home. If we come, you can make us leave with a word but never, ever invite us," he had said.

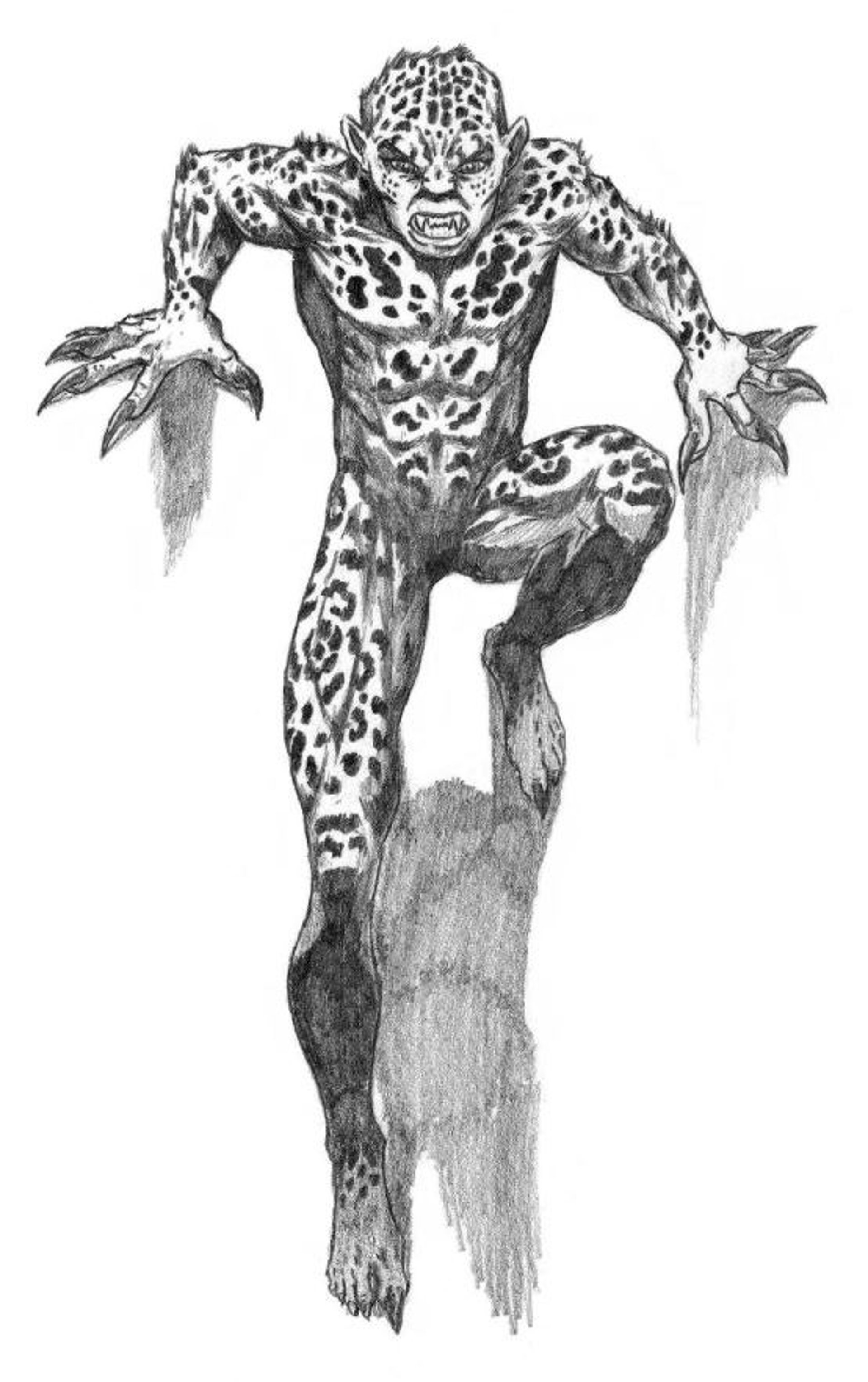

Tonight, I speak with a wizened Kanaima who offers me bloodied deer when I enter the dark crevice of his domain. We speak for hours. On the outside, he appears to just be an older, native man. When I tell him this, he laughs and offers to show me something.

I watch with interest as he brings out a furred blanket, shouldering it until he dissolved beneath it. At the edge of my seat, I watch as the blanket transforms. The fur melts onto the old man’s skin, like cheese slice on a hot tawah, the yellow and black fur dripped in a strange gluey material – coating ever inch of his crouched body. At the end of it, he appears the size of a man seven feet tall with menacing eyes of red.

“Wow.”

In this form, he tells me of how he came to have his skin. “I was an arrogant hunter. I sought to hunt a witch and she ensnared me as this until I can no longer walk this earth.”

“How long have you been this way?”

“However long I can remember.”

I’m about to ask him how long that’s been, when the entrance of his domain is darkened by the familiar spindly figure of the moonwalker. The Kanaima drops his head, smiling at me. “We will continue this later.”

When we step outside, I look up at the moonwalker.

“I didn’t think I’d see you again.”

The moonwalker hums and I realize we’re going back home. “We will see each other always, Archivist. I am your guide.”

“Some guide. Did you know the mermaid almost ate me?”

“I did say no fish.”

Rolling my eyes, I keep my tongue still for the rest of the journey. In the morning, I awake to a scream so deeply personal and guttural that it throws me from my bed. Scrambling for the source, I find myself staring at my father holding Pa close and weeping like a child.

When someone dies in their own residence, you wait for the police to come. Unfortunately, they take four hours even though they are just two corners away. The coroner says he passed during the night, around three – around the time I left. He’d had a seizure and no one was around to help him. He’d died while I was out, shackled to a tome and to monsters.

He’d died alone and I only have myself to blame.

***

The repass is held at my aunt’s home in town. Not far from the police grounds in Kingston. It gives the illusion of safety. There are weeping faces and trembling stories. The monsters have not called to me for five nights. Probably out of pity for me. Meanwhile, I have not slept for any.

Pa was ninety-seven. His death is no more my fault than the rain. It is strange how days can provide distance and I'm yet to shed a tear. My entire soul seems to have gone missing, leaving behind a simple husk.

I wonder if I have become a monster. What kind of person doesn't cry at the death of their beloved grand-father?

The couch dips and I cast my eye to the side of me. I don’t recognize this man... but then again I didn't recognize most of these people. He is slender, long limbed and wears shades even though its evening.

“I’m sorry for your loss.”

“Thank you.”

“I worked with Arnold for years.”

I feign interest. “Are you a doctor?”

“Not a doctor. You come from an exceptional family.”

“Thank you.” What else is there to say?

I try to look away from the man. A polite signal that I'm done with the conversation. But there's something about him. The odd stench of familiarity. The man lowers his shades. Familiar moon eyes peer into me with the intimacy of family.

The tears finally come, filling my eyesight and rolling down my cheeks.

“We will see you later.”

Later is the tenth night. The tome is lighter, and my feet no longer bleed during my trek. The darkness is a comfort and the coziness of legacy settles inside my vessel. My soul returns to me with the pride of knowing I am continuing along an honoured path.

And fulfilling a family legacy.

contact@desserttalesgy.com

592-632-4636

© 2025. All rights reserved.